Sabina – Reconstructing a Research

Sabina

Reconstructing a Research

Audio guide

An excerpt in 18 chapters

photographs, various formats,

archival pigment prints

/

Narration as audio guide,

18 stations

Narrator: Lena Franzen

sound: Roman Strack

About a visit to the museum

1.1 Moritz Wullen, Die Deutschen sind im Treppenhaus (The Germans are in the Stairwell). Cologne: DuMont, 2002. Page 24.

1.2 Sabina von Steinbach, Frieze by Otto Geyer, 1870—75, stairwell of the Alte Nationalgalerie, detail.

1.3 Sabina von Steinbach, Painting by Moritz von Schwind, 1844, Collection Alte Nationalgalerie, third floor.

1.4 Signage. Collection Alte Nationalgalerie

Translation audio guide

She no longer remembers, W. said, which depiction of Sabina von Steinbach first caught her eye at the Alte Nationalgalerie. However, from her entries in the red notebook at the time, it was clear that, although she must have initially walked past the frieze of figures in the stairwell to reach the picture gallery on the third floor, nevertheless she had first noticed the painting by Moritz von Schwind. The depiction of a sculptress at work in a 19th-century painting had seemed highly unusual to her, and she had also never heard of the artist’s name before, which was given as the work’s title.

Probably she would not have been further interested in Sabina von Steinbach if she had not finally turned her gaze upward to the frieze of figures in the stairwell while leaving the museum, if she had not read that name again, there, in golden letters, under a figure of a woman holding sculptor’s tools. At that moment and in that place, there had been nothing to suggest that Sabina von Steinbach could be a fabrication.

The individuals on the frieze had been selected from politics and the arts and sciences, reaching as far as the then-present times of 1870-75, when sculptor Otto Geyer was commissioned to create the frieze for the Nationalgalerie. Among those depicted are only four women. The medieval sculptress Sabina von Steinbach is the first and only one of them who was not of noble descent. She is also the only woman on the frieze, according to W., who pursued a vocation and who, as W. had at least initially assumed, found her way into this canon thanks to her merits as a sculptress. It was only much later that she realized that Sabina must have been chosen for the frieze for different reasons, and that these reasons had far more to do with politics than art.

About reproductions, copies and originals

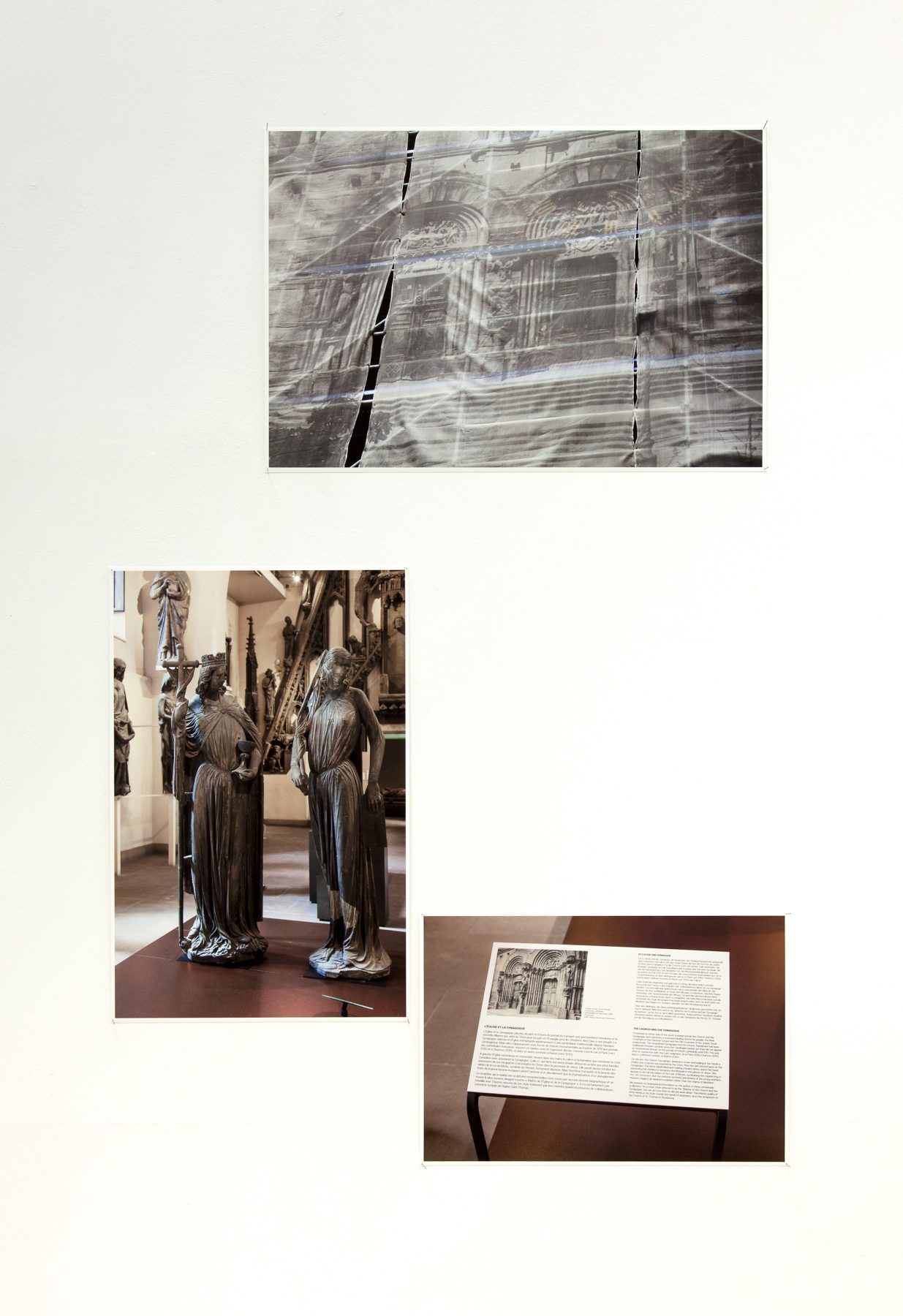

2.1 Ecclesia and Synagoga. Original sculptures relocated from Strasbourg Cathedral, circa 13th century, Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

2.2 Photo tarpaulin. South transept portal of Strasbourg Cathedral, July 17, 2018.

2.3 Caption on Ecclesia and Synagoga. Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Translation audio guide

Every time she went to Strasbourg, W. said, the entire south transept portal of the cathedral had been concealed behind a tall wooden fence and even taller scaffolding. All that could be seen of the portal itself was a huge b/w reproduction printed on fabric, fluttering on the scaffolding and appearing more faded than before with each subsequent visit.

Just as the scaffolding always stood there unchanged, the original sculptures of the Ecclesia and Synagoga, attributed by so many sources to Sabina, can still be seen in the museum opposite the cathedral, positioned close to one another, only a few hundred meters from the site they were originally intended for some 700 or perhaps 800 years earlier. There, they flanked the south transept portal of the cathedral, its main entrance at the time, on the left and right. The sculptures could not have been overlooked by all the city’s inhabitants, most of whom must have frequently crossed this central square.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, however, at the portal itself there are only copies of the real sculptures, which W. was only familiar with from photographic reproductions. To this day, she regrets that she never saw the sculptures in their original context, but only ever stood in front of this construction fence.

During her first visit to the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, to her confusion, she did not encounter a single mention of the sculptress Sabina any-where, and her following research did not yield any conclusive findings either. On the contrary, this research had plunged her into even more complex perplexities, which – and this presented perhaps a realization after all – she could not resolve and transform into any lucid, credible assertions. It was not only the distant time of origin of the Strasbourg Ecclesia and Synagoga that hampered an exact reconstruction of the events, but also all the contradictory voices from the following centuries, which, through their conflicting statements about the sculptures, their meaning and their relationship to Sabina, made W. doubt more and more the possibility that a single true account could be derived from the various older and more recent historiographies and established beyond doubt as objectively valid.

At that moment, she recalled, she had seriously considered abandoning her research, which had only just begun; and perhaps she would have done so had she not stumbled upon another representation of Sabina in the stairwell of the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe two days later, already on her way back to Berlin.

About a depiction of Christ with a rare skin disease and later on very blond hair

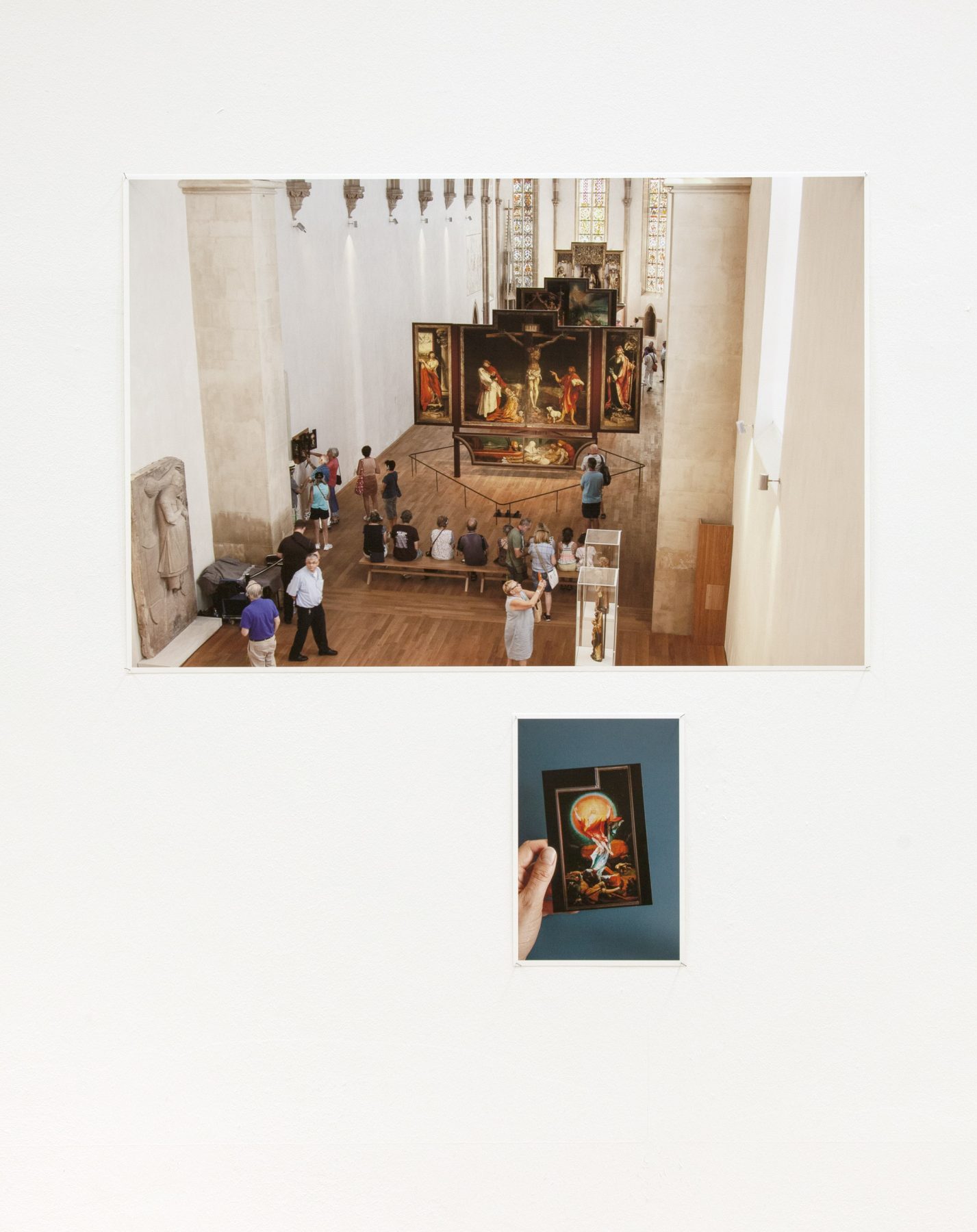

3.1 Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, 1512—1516. Musée Unterlinden.

3.2 Postcard of Resurrection of Christ, Isenheim Altarpiece.

Translation audio guide

The sight of this Christ came as a shock to her, W. said, yet at the same time, the moment she saw him for the first time, she was overcome with emotion, which she couldn‘t put into words. The reason for this, she believed now as then, had not been the graphic portrayal of a horribly martyred and disfigured body, but something else that could perhaps be called an aura, no doubt stimulated by the sacral setting of the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar. But beyond that, it was the altar itself that had given rise to this reaction: in a sublime yet uncanny way, the sight of it touched something in her, the existence of which she had so far only known vaguely and indeterminately.

However, this moment had been – of course – short-lived. She had turned on the audio guide and was circling the altar, listening to the warm, female voice in her ear explaining what she had been looking at. The rash that afflicted this Christ, adding to the ordeal of crucifixion another almost unbearable suffering, was commonly known as St. Anthony’s Fire, a widespread disease in the Middle Ages. Today, we know that it was caused by a fungus, resulting in the most severe pain, cramps, skin rashes, and vascular constriction to the point of necrosis of the limbs. There was hardly a cure for it.

The infirmary of the Antonite monastery in Isenheim, for which the altar had been made, was especially dedicated to the treatment of those suffering from this very disease. At the beginning of their admission to the infirmary, the sick were led to the altar, where the sight of a crucified Christ who was also afflicted by St. Anthony’s Fire and who, beyond that, had suffered so much more than them, was intended to uplift the patients spiritually and to strengthen them to endure their own suffering. It was only through the information provided to her by the audio guide’s voice, W. said, that she realized that the Isenheim Altarpiece had been a distinctly contextual and site-specific commissioned work, which today, of course, and for a long time now, could be marveled at far removed from that site and context.

Little was known about the history of the altar‘s creation, according to the voice of the audio guide. The identity of the creator of this “unique artwork” had also been disputed for a long time, until 2007, when contemporary art historians had agreed that the artist, known by the name Grünewald, must have been the painter Mathis Gothardt Nithart. According to W., she was no longer sure whether the audio guide’s voice had considered this identity to be firmly established or whether its intention was to provide insight into the current state of an ongoing debate.

Thus informed, she continued to wander through the hall, looking at the other wings of the altar on display. The scene of his resurrection appeared to her quite different from the crucified Christ, though no less surprising and just as extreme. W. took a postcard from her desk showing a serene, floating, very blond and very fair-skinned Christ. In this poorly printed miniature, he looked even more comic-like and even more psychedelic than she remembered him, she said, adding that it seemed both strange and logical to her to portray this Savior as an ideal of beauty for those he had been created for, unconcerned about historical plausibilities. From her own perspective, however, which was anchored in this present, she wondered what it would lead to if stories were always told in such a way that they confirmed one’s own worldview and seemed as useful as possible in conveying certain ideas and ideals.

She often thought about the depiction of Sabina in the frieze of figures in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin in connection with the Isenheim Altarpiece, which was, of course, a very personal connection, that arose simply from the fact that she would probably never have seen the altar or thought about it until today, if she had not begun to occupy herself with Sabina.

In the course of her research, she had to learn that her ideas were not in line with the ideas of those who had included Sabina in the canon at the Alte Nationalgalerie. The longer she had spent looking into Sabina, the more complicated matters had become; the more she had learned, the less tangible Sabina had turned out to be. Not infrequently, she thought that it might have been more useful for the sake of her own sense of self if she had been content with the Alte Nationalgalerie’s version of sculptress Sabina and simply rejoiced in the fact that already 700 years ago there lived a woman who pursued an artistic vocation.

Wherein, among other things, it becomes apparent that an artist also copies himself sometimes

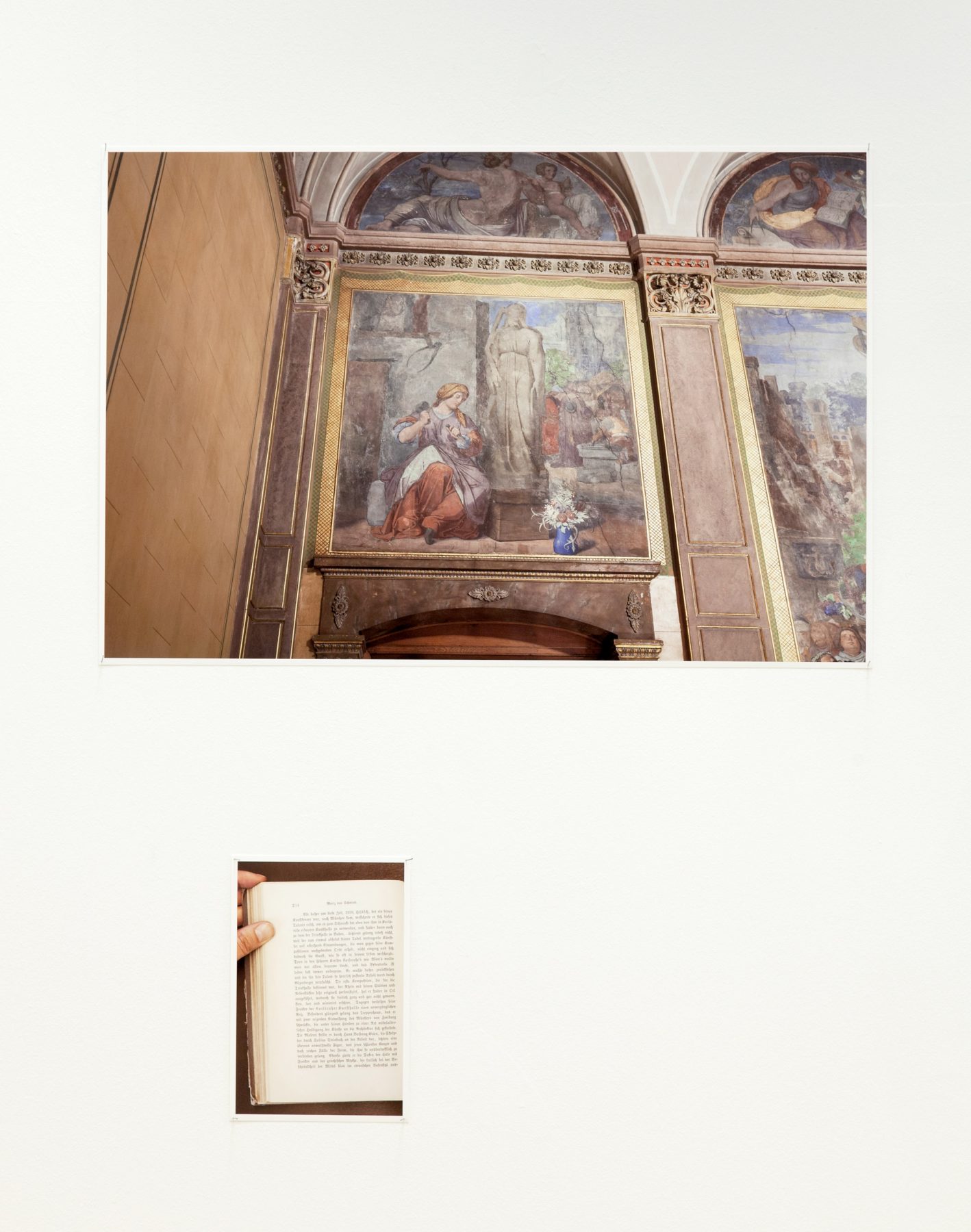

4.1 Sabina von Steinbach. Fresco by Moritz von Schwind, 1843, first floor stairwell.

4.2 Friedrich Pecht, Deutsche Künstler des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts. Studien und Erinnerungen von Friedrich Pecht. (German Artists of the Nineteenth Century: Studies and Memoirs). Nördlingen: Druck und Verlag der Beck’schen Buchhandlung, 1877. Page 214.

Translation audio guide

When she visited the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe in the summer of 2018, she was already on her way back from her first trip to Strasbourg, W. repeated. There, at the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, she had seen the Ecclesia and Synagoga sculptures in the original for the first time. She remembers that she was in a doubtful, confused mood when she got off the train in Karlsruhe to see – for the sake of completeness rather than out of higher expectations – the Sabina fresco by the painter Moritz von Schwind at the local Kunsthalle, which had been completed a few years prior to the almost identical Berlin painting.

Eventually, the sight of the fresco had a strange effect on her. It seemed to her that the mere contemplation of Sabina, depicted as a sculptress, led to the possibility of Sabina’s real existence becoming imaginable again, after she had actually almost given up on it during her visit to the museum in Strasbourg.

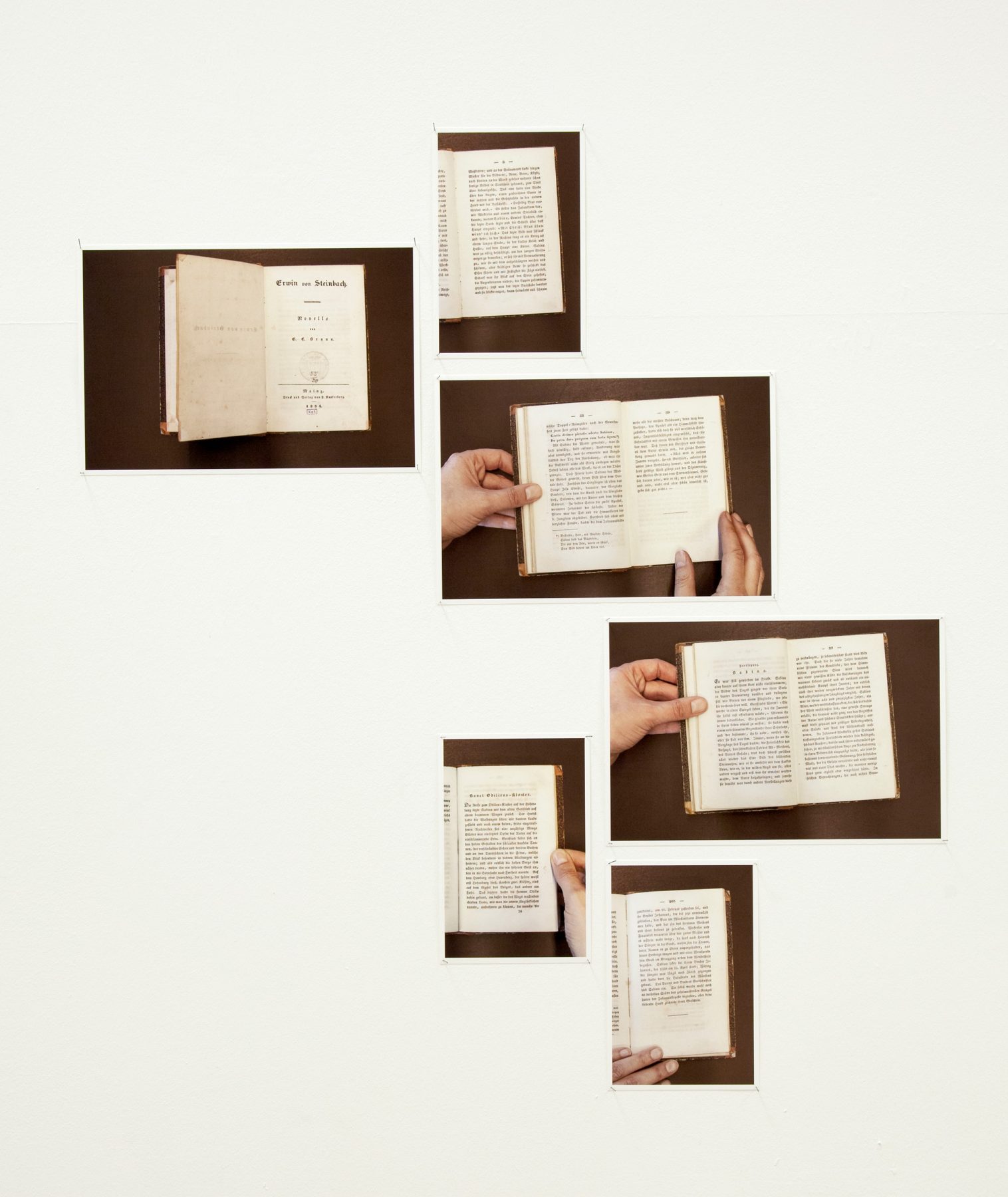

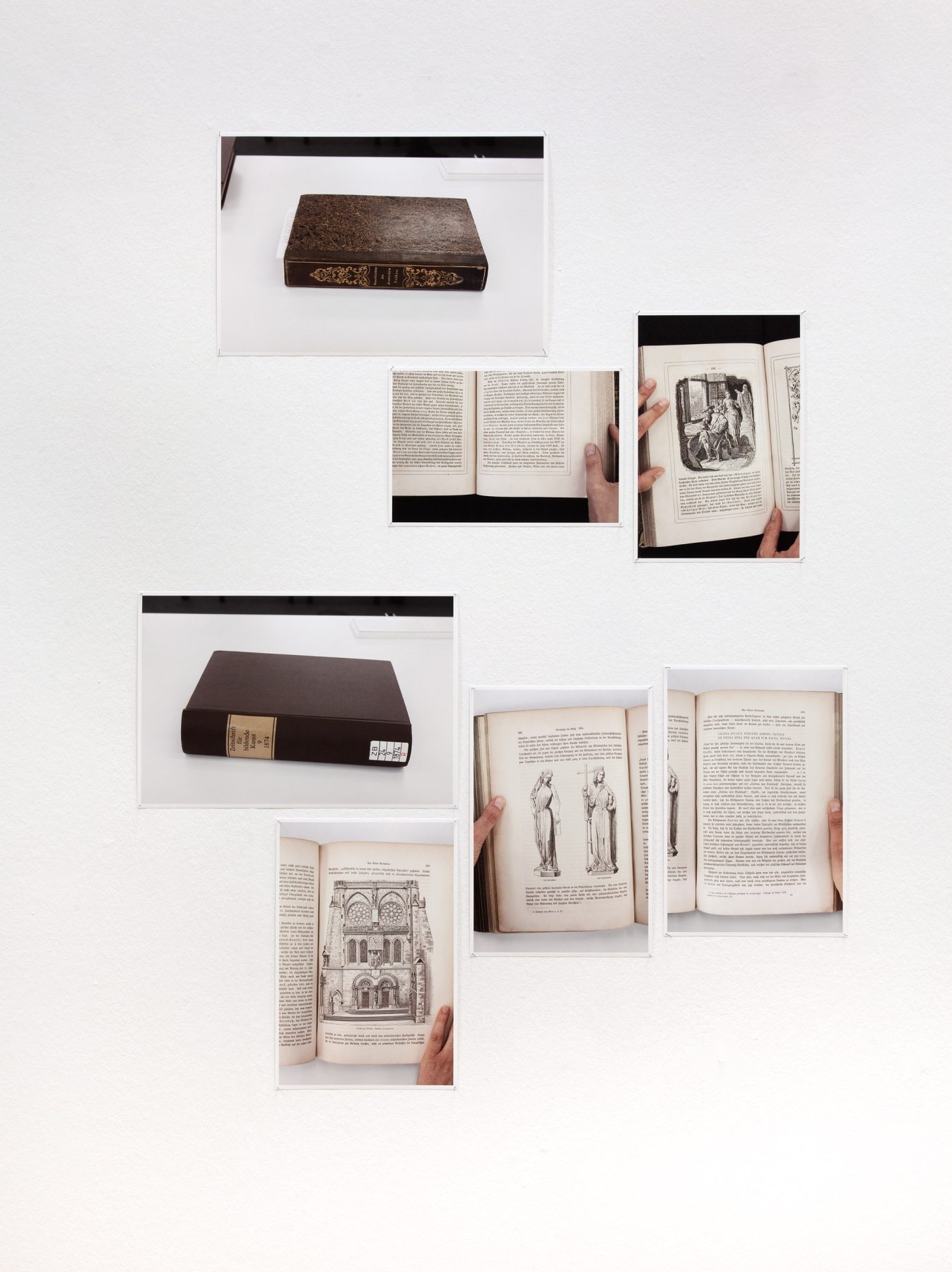

Wherein a long novella is studied repeatedly and in great detail

5.1—5.6 Novella Erwin von Steinbach by Georg Christian Braun. Mainz, 1834. Title page and pages 5, 36—37, 57—58, 185 and 203.

Translation audio guide

The first of a whole series of libraries she visited to peruse documents, art-historical essays, literary works, historical treatises and chronicles that mentioned the sculptress Sabina von Steinbach was the Municipal Scientific Library in Mainz, W. said.

It is possible that she devoted herself to Braun’s novella with such intensity because it was one of the first books for her in which Sabina played a leading role as a person and therefore seemed alive to her. But now W. realized her early fixation on Braun’s novella had been a mistake. Although she knew, of course, that this Sabina was an altogether fabricated figure, she had not been able to fully internalize this. Again and again she would later find herself giving the Sabina of her own imagination the characteristics of Braun’s Sabina, just as she had not infrequently and unwittingly given her imagened Sabina the features of the Sabina in Schwind’s painting. At some point she also realized with some dismay that her thorough reading of Braun‘s novella had determined the direction her further research had taken far more comprehensively than she had been aware of for the longest time. And that, if one thought about it well, would be all the more astonishing, since she had felt neither the novella to be a success, nor the portrayal of Sabina there to be a good one.

The German-language texts about Sabina from that period she had since read made Braun’s novella seem exemplary of the turgid, nationalistically tinged tone she had found predominantly in 18th and 19th century texts.

Braun’s blending of fact and fiction had indeed become increasingly confusing to her. Her attempt to separate the truths from the fabrications had literally given her a headache. The situation was complicated in particular by the fact that Braun treated certain matters as historical fact, which may have been generally regarded as such at the time, but not anymore in today’s context. For Braun, Sabina von Steinbach had naturally been a historical figure, and so for him the invented love story between Sabina and Johannes Weckerlin had taken place between a real and an invented person. However, against the background of the facts currently considered valid, one would have to say that this was not a case of mixing facts with fictions, but of mixing one fiction with another fiction, even if the author had not been aware of it.

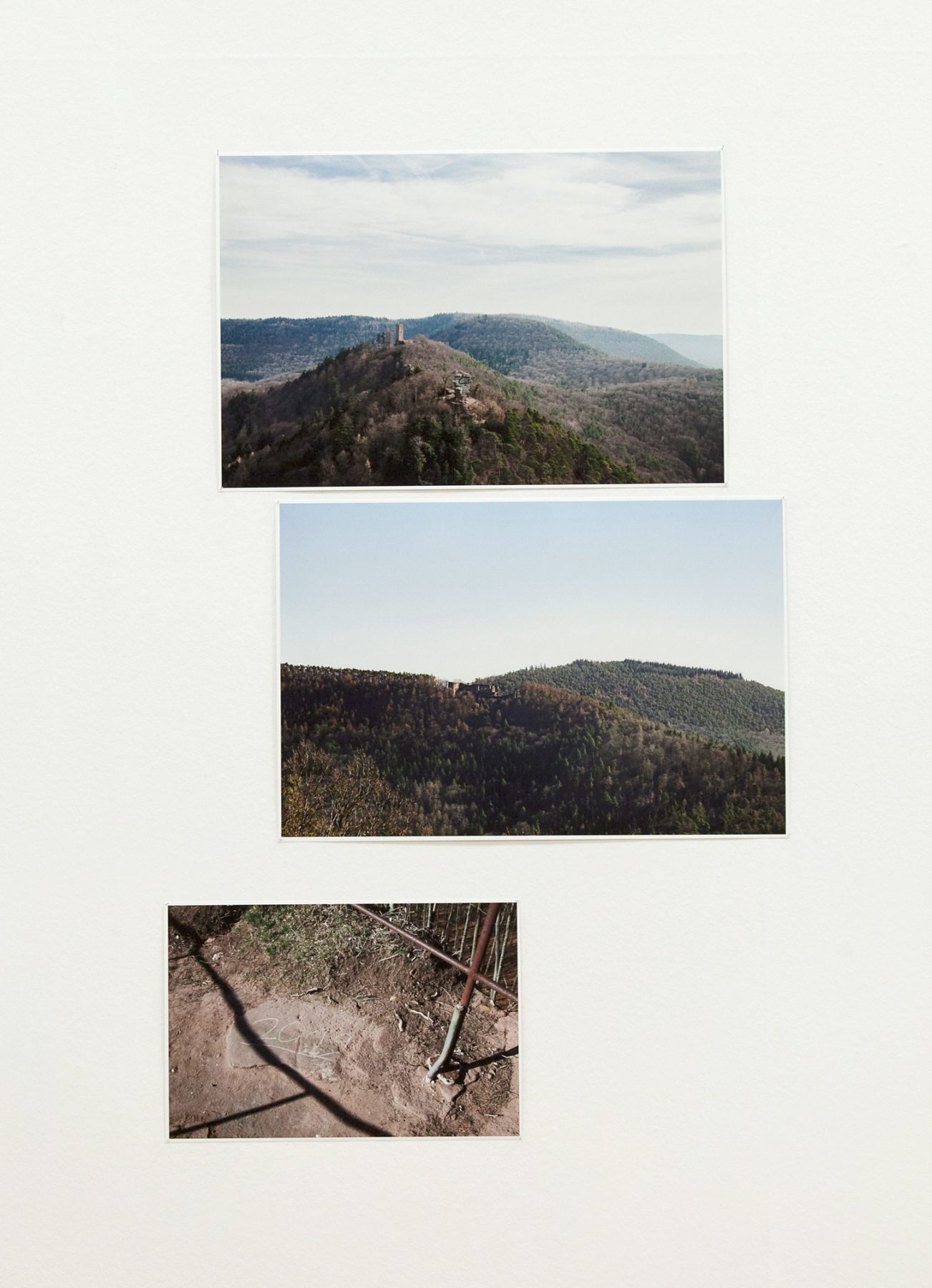

About hikes and castle ruins

6.1 View from Trifels Castle of the Anebos and Scharfenberg castle ruins. Southern Wine Route, Rhineland-Palatinate.

6.2 View from the Ramburg castle ruins of the ruins of Neuscharfeneck Castle. Southern Wine Route, Rhineland-Palatinate.

6.3 Detail of the ruins of Wasigenstein Castle. Département Bas-Rhin, Région Grand Est (formerly Région Alsace until December 31, 2015).

Translation audio guide

For reasons that no longer seemed as plausible to her today as they had then, W. recounted, at some point, she began to seek out all the castle ruins located in the mountainous forests near Strasbourg, referred to as the Northern Vosges on the French side and as the Palatinate Forest on the German side of the border. Her notes from that time in her black and her green notebook now seemed to her to be partly cryptic, full of allusions and convolutions, and, again and again, page-long descriptions of nature interrupted her reflections on Sabina. She herself was amazed at how imprecise and sometimes even confused some of these records tended to sound.

It is true, however, that the sculptress Sabina could (always assuming she existed) theoretically have stayed in one or even more of these castles. Most of them were built around 1200, so they were actual buildings during Sabina’s lifetime – but today, and for several centuries already, not much is left of them. Almost all of these castles were destroyed in the course of the Thirty Years’ War, and their ruins have been popular destinations for excursions, especially since the 19th century.

It had to be futile, W. said, and this certainly had been clear to her at the time, to search in those ruins for concrete traces of past inhabitants or even Sabina. And yet, looking for these places, whose heyday and time of origin were so closely linked to Sabina’s lifetime, seemed significant to her in constructing a context in which she could imagine Sabina. The ruins evoked in her a vague sense of time that had actually passed, whereas she had felt nothing but presence in the woods through which she had come to them.

Wherein it turns out that some reading can lead to great confusion

7.1 Die Geschichte des deutschen Volkes, book by Eduard Duller, 1840, Reading Room Collection, Baden State Library.

7.2—7.3 Eduard Duller, Die Geschichte des deutschen Volkes von Eduard Duller. Mit hundert Holzschnitten nach Originalzeichnungen von Ludwig Richter und J. Kirchhoff. (History of the German People: With one-hundred Woodcuts after Original Drawings by Ludwig Richter and J. Kirchhoff). Leipzig: G. Wigand, 1840. Pages 255 (detail) and 256.

7.4 Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst (Journal of Fine Arts), Volume 9. Leipzig: Seemann, 1874. Reading Room Collection, Baden State Library.

7.5—7.7 Alfred Woltmann, Streifzüge im Elsaß. VIII. Das Straßburger Münster, (Strolls through Alsace. VIII. Strasbourg Cathedral) Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Volume 9, 1874. Pages 332, 333 and 329.

Translation audio guide

She had the Reading Room Collection of the Baden State Library in Karlsruhe all to herself, W. said. Perhaps this was why she had found the presence of the valuable or perhaps merely rare books surrounding her on high shelves so strangely intimidating. Eduard Duller’s History of the German People from 1840 was lying in front of her. According to him, Sabina von Steinbach was a historical figure: She is mentioned on page 255, in only a short paragraph, as master builder Erwin von Steinbach’s daughter. Duller, as if unnecessary, provides no source, as if the existence of the named individuals was so assured and self-evident that no proof was needed. On the following page, Sabina’s existence is manifested once again. In a depiction together with Erwin showing him bent over a drawing of his design for the western façade for Strasbourg, she can be seen working with hammer and chisel on a large sculpture, presumably the apostle attributed to her.

Alongside Duller’s book, she had opened an anthology of the Journal of Fine Art from 1874, in which she discovered the article Strolls through Alsace by Alfred Woltmann. He also mentions Sabina, but does not believe in her existence as Sabina von Steinbach. He explains in detail that Sabina could not have been the daughter of Erwin, but, as Savina, must have lived many decades earlier. Woltmann names Louis Schneegans as the historian who exposed this misconception, which was based on Daniel Specklin’s chronicle.

At the time, she said, she had been somewhat perplexed as to how she could tell the difference beyond a shadow of a doubt between historical fiction and events that had actually taken place. There in the library, amongst all those books that promised so much knowledge, she was suddenly overcome by a sense of unease that it was quite possible to research through half a library and still gather false facts. When she took a photo of the illustration of Strasbourg Cathedral’s south transept portal in Alfred Woltmann’s essay, she fell into a state of confused agitation because of the contradictory statements she had previously read. Possibly for this reason, she paid no attention to the sculptures depicted on the walls to the left and right of the portal. Only several months later, when she revisited the material, she noticed these details, or rather: she found herself in a position to recognize and classify them. On the left side there was a sculpture created by Philippe Grass in 1864, representing Sabina von Steinbach, and on the right side there was a sculpture created in 1842 by Andreas Friederich of master builder Erwin von Steinbach.

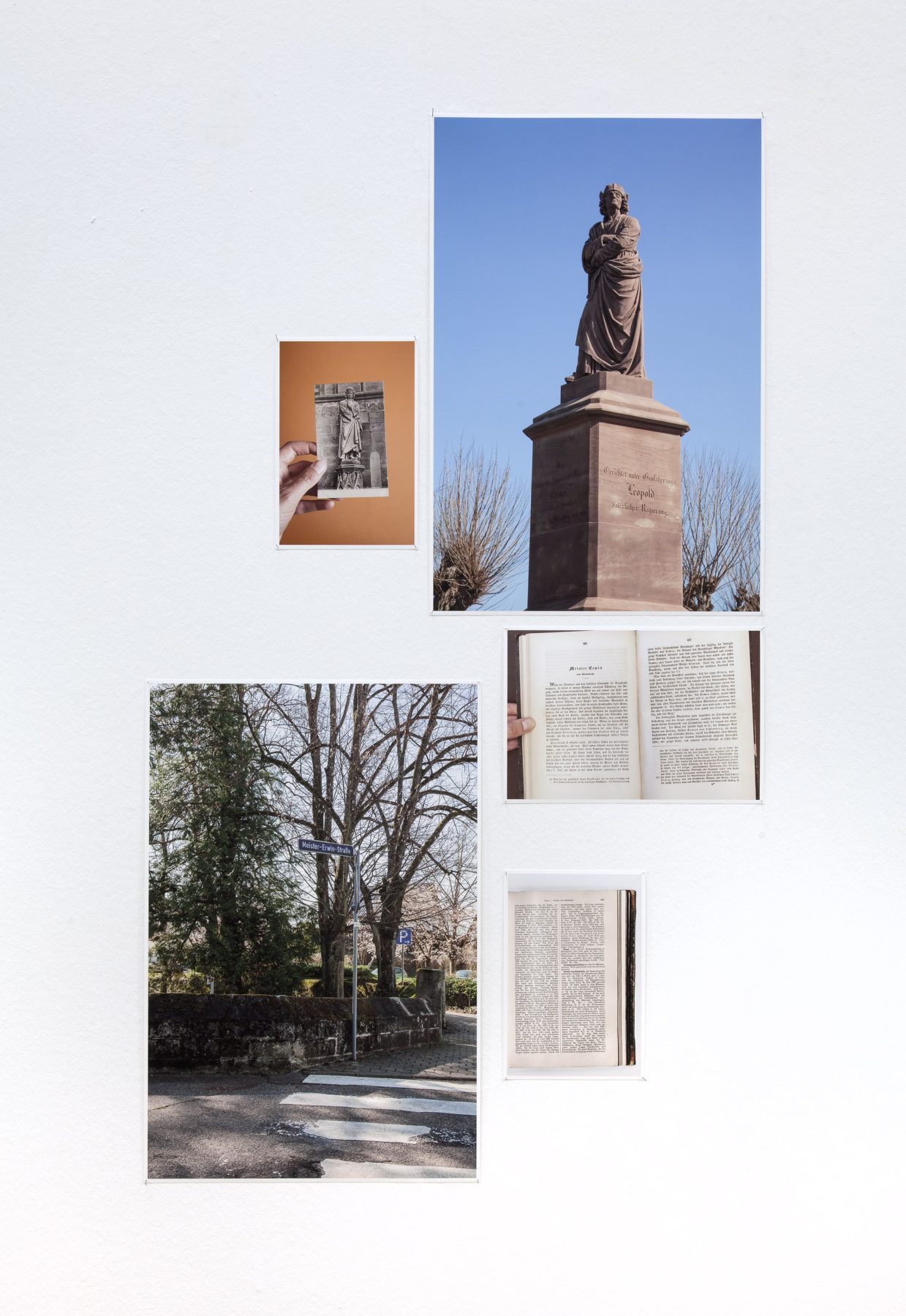

Leading to a nondescript little town with a monument sure of itself

8.1 Postcard of Monument of Meister Erwin in Strasbourg by Andreas Friederich, 1842.

8.2 Monument of Meister Erwin by Andreas Friederich, 1844, Steinbach.

8.3 Allgemeines Handbuch der Freimaurerei. Dritte, völlig umgearbeitete und mit den neuen wissenschaftlichen Forschungen in Einklang gebrachte Auflage von Lennings Encyklopädie der Freimaurerei. Herausgegeben vom Verein deutscher Freimaurer. Erster Band. A—L., (General Handbook of Freemasonry: Third Edition of Lenning’s Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, Completely Revised and Brought into Line with New Scientific Research). Volume 1, A—L. Leipzig: Max Hesses Verlag,1900. Page 263.

8.4 Street named after Meister Erwin, Steinbach.

8.5 Joseph Bader, Das malerische und romantische Baden von Dr. Joseph Bader. Mit 48 bis 54 Stahlstichen. (The Picturesque and Romantic Baden by Dr. Joseph Bader: Including 48 to 54 Steel Engravings), Volume 1. Karlsruhe: Kunstverlag, 1845. Pages 66 and 67.

Translation audio guide

The village of Steinbach was first documented almost 1000 years ago, and has officially belonged to Baden-Baden since 1972. For a while, W. said, she had thought that by investigating Strasbourg master builder Erwin von Steinbach, she might also learn something about his possible daughter Sabina. She had assumed that whatever traces led to him would inevitably also lead to her. If Erwin was born in the village of Steinbach, as many documents stated, then Sabina must have roots there as well, according to W.’s idea, which she admitted seemed rather naïve from her present perspective. Like all traces concerning Sabina, which at first had appeared to be clear and unambiguous, this one also turned out to be more and more diffuse and doubtful the longer she looked into it. After a first village called Steinbach, other villages by the same name surfaced, which could have been the birthplaces of the master builder – or, as it turned out, none of them.

While she was circling the Erwin monument in Steinbach again from her desk on the basis of photos she had taken of it, W. said, she involuntarily had to think of all the documents, papers and essays she had pored over in the various libraries. Her memory of these documents was unsystematic, arbitrary and incomplete. What she did remember today was only one of many momentary impressions. She remembered Joseph Bader, who wrote in 1845 that Erwin built the Cathedral in Strasbourg and that he hailed from Steinbach near Baden-Baden. She remembered Alfred Woltmann’s essay from 1874, in which he claims that other Steinbachs could also be candidate birthplaces of Erwin. She remembered Specklin, too, of course, whose chronicle may have been the first to document the Erwin inscription with the addition “von Steinbach.” And through Specklin she remembered the writings of Schadaeus, which she had also sighted in the University Library of Heidelberg and in which, on one page, a correlation surfaced between the two inscriptions referring to Erwin and Sabina, which used to be affixed to Strasbourg Cathedral but have now disappeared.

The Erwin sculpture in Steinbach, she would later learn, was not the first by the sculptor Andreas Friederich. The similarity between the sculpture, which had already been erected in 1842 in front of the Strasbourg south transept portal, and the monument on the outskirts of the small town of Steinbach was striking. It was probably this very similarity, W. said, that once again had made her ponder the significance of choosing a site for a monument or sculpture in a public space. As much as the two Erwin sculptures resembled each other, their sites were very different: one in the center of Strasbourg, in front of one of Europe’s most important cathedrals, the other one on the outskirts of a minuscule town, behind a cemetery, so far off that hardly any visitor would notice the monument unless they were looking for it.

This remote location seemed strangely contradictory to her at the time of her visit. On the one hand, the monument was exceedingly immodest in size and gesture, and even the engraved inscriptions left no doubt as to which important person was supposed to be a famous son of the village. On the other hand, the monument was relegated to the outermost edge of the community. Nobody, according to W., would simply pass by there; the hill behind the cemetery was not part of daily life, as if the people of Steinbach had no interest in it.

It was only during later research on the monument that she realized that it was by no means the residents of the village who had commissioned it. Like the entire story of Erwin, it was introduced to them from outside: The sculptor Andreas Friederich himself had applied for permission to erect a monument of Erwin in Steinbach, designed by him, and he had acquired the plot of land on which it stands to this day from the local municipality.

Allegedly, W. added, it became known after the unveiling of the monument that a Masonic lodge had donated it. She had read about it first in a short article on the Internet and later also in a reference work on Freemasonry. In the latter, however, Mainz had been mentioned as Erwin‘s birthplace, which she had not read anywhere else.

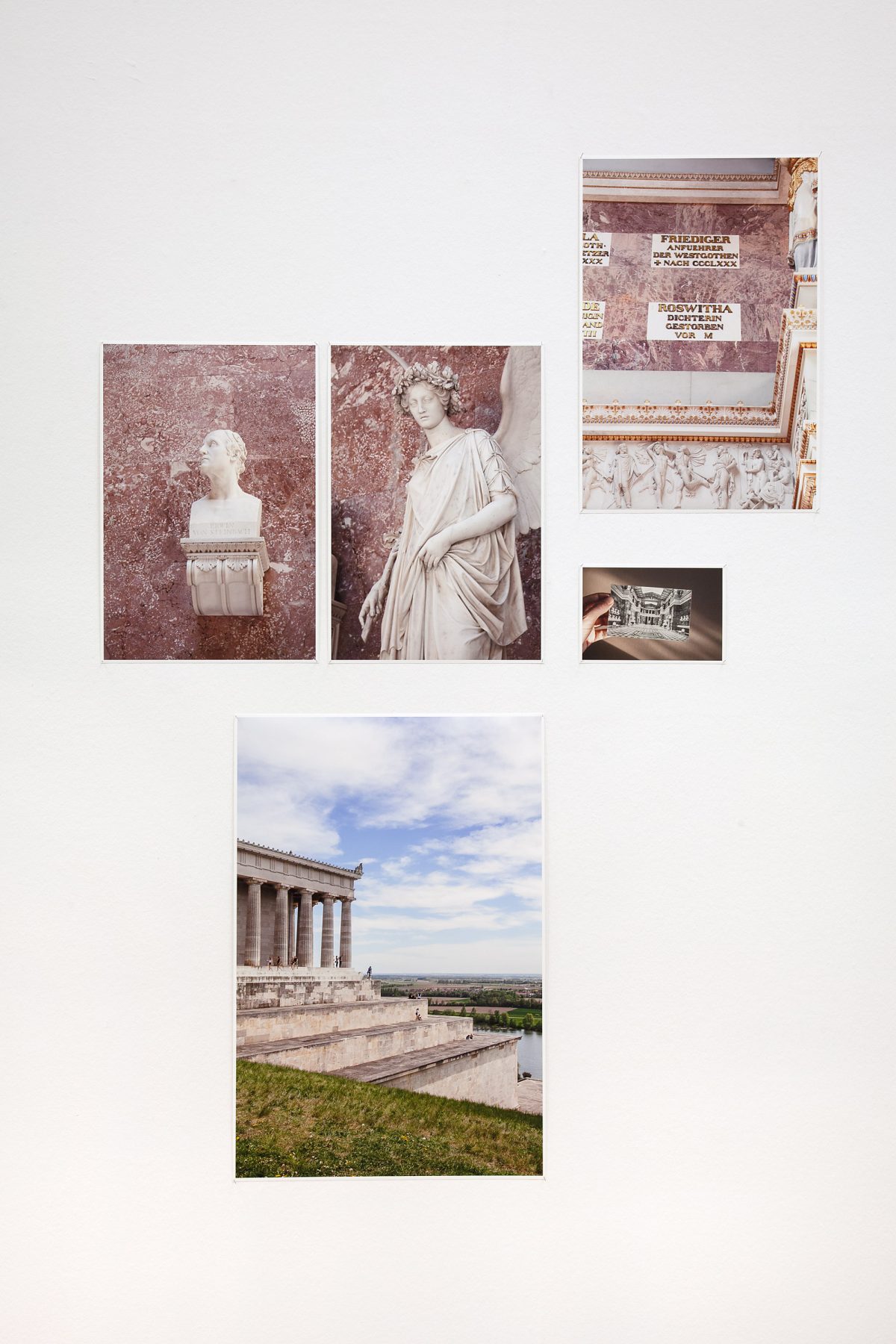

Wherein a woman other than the one in question is found

9.1 Bust of Erwin von Steinbach, Walhalla Memorial.

9.2 Sculpture of the Goddess of Victory, Walhalla Memorial.

9.3 Walhalla interior, postcard.

9.4 Commemorative plaque of Roswitha, Walhalla Memorial.

9.5 At the Walhalla.

Translation audio guide

It was not her intention to be impressed by the sight of the Walhalla, W. said. It may have been thanks to the early morning hour when she left her pension, because of the empty highway, because the much earlier than expected appearance of the memorial on a still distant hill, because of its absurd size, which had made it seem so unrealistic, and certainly also thanks to the rays of sun, which bathed the building in such a dramatic, red-golden light that W. was indeed breathless for a moment, at least as she remembers it. This building had an effect on her, entirely against her will, that must have perfectly corresponded to the intention of its builders.

She involuntarily compared the Walhalla with the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, which likewise resembled a Greek temple. The comparison was indeed obvious: in both places, a frieze as well as busts and commemorative plaques assembled together personalities who were regarded as significant for a German historiography and the formation of its identity in the 19th century. However, the Walhalla memorial was already inaugurated in 1842, initiated by King Ludwig I, about 30 years before the opening of the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, whose initial planning, however, had begun even earlier than that of the Walhalla. Unlike the frieze in the stairwell of the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the arrangement of the busts in the Walhalla does not follow a chronological order. The selection and arrangement might at first seem arbitrary, incomplete, subjective even. And this impression was not entirely inaccurate. Whereas the original selection followed the personal preferences of King Ludwig, today all Bavarian residents are given the opportunity to nominate new inclusions. One of the more recent additions is the bust of Sophie Scholl, erected in 2003, and only a few weeks after W.’s visit in summer 2019, a bust of Käthe Kollwitz was added. It was remarkable, although not surprising, W. said, that the addition of women to the hall of fame has been increasing since the late 1990s. However, they were still vanishingly few, she reckoned during her tour of the hall at the sight of all the men’s heads, which are shielded by six sculptures of winged goddesses of victory, which almost doubled the number of representations of female figures.

On her way out, when she had already mentally withdrawn from the hall, similar to the time when she had discovered Sabina in the stairwell of the Nationalgalerie, she once again looked all the way up. High above the rows of busts, on a double row of commemorative plaques, she discovered yet another woman: an artist who is said to have lived over 1000 years ago and whose existence, a quick Internet search revealed, was almost as controversial as that of Sabina. When W. had finally descended the long flight of steps back to the parking lot, her thoughts were focused more on this poet called Roswitha than on Sabina. She still vividly remembers the urgent need she felt the entire way back and beyond to learn more about this woman, about her sparsely documented life and her only partly preserved body of work.

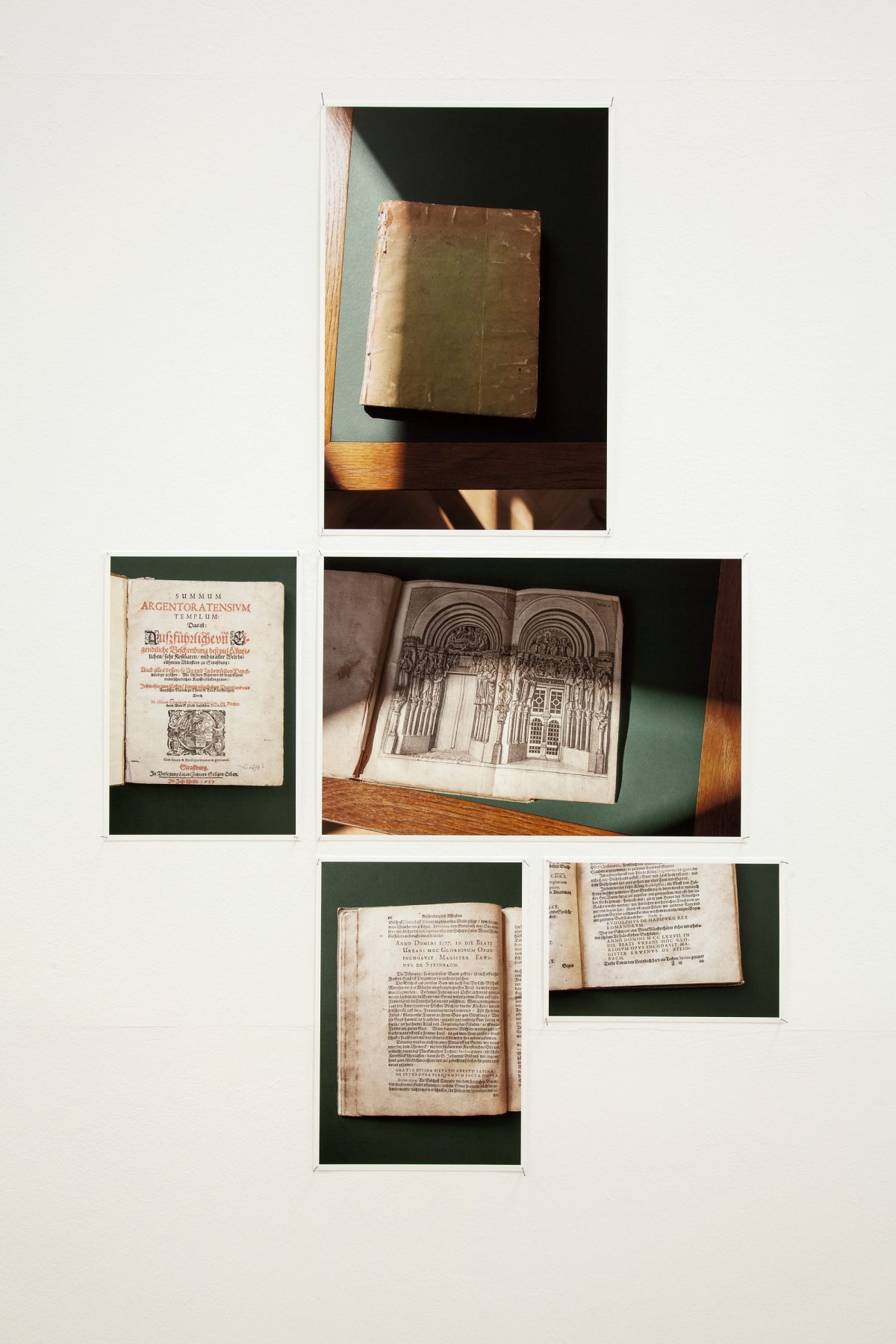

Manuscript Reading Room About a little four hundred year old book of great impact

10.1 Schadaeus’ publication from 1617, book cover, Manuscript Reading Room, Heidelberg University Library.

10.2 Title page of Oseas Schadaeus’ Summum Argentoratensivm Templum:

Das ist: Außführliche vn Eigendtliche Beschreibung deß viel Künstlichen, sehr Kostbaren, vnd in aller Welt berühmten Münsters zu Strassburg (Summum Argentoratensivm Templum: That is: A Detailed and Original Description of the Highly Artful, Very Precious, and World Famous Strasbourg Cathedral). Strasbourg: Zetzner, 1617.

10.3 In Schadaeus: Isaac Brunn, Engraving

No. 6: South transept portal of Strasbourg Cathedral.

10.4 Schadaeus, page 14: Commentary on the Erwin and Sabina inscriptions at Münster Cathedral (both no longer extant).

10.5 Schadaeus, page 45 (detail), mention of Sabina as daughter of Erwin.

Translation audio guide

Isaac Brunn’s engraving, first printed in Schadaeus’ 1617 publication, is in fact the one pictorial source generally referred to regarding the condition of the south transept portal of Strasbourg Cathedral before it was largely destroyed during the French Revolution. It is only through this engraving that the existence of the Latin inscription, held in the hands of one of the apostles and indicating Savina as the creator of the sculpture, has been handed down. Schadaeus refers to her as the daughter of the master builder Erwin von Steinbach, even though this is not clear from the inscription itself.

W. was holding her yellow notebook in her hand while at the same time leafing through the photographs of Schadaeus’ writings she had taken in the manuscript reading room. From the temporal distance of past months filled with other tasks, she realized with some concern how deeply she had, at that point, already become entangled in speculation and how much her brain had begun to develop its own wild theories about the person Sabina. With a mixture of wistfulness and uneasiness, she recalled that this activity had brought her joy. It was delightful to engage with possible versions of Sabina, ones that not only seemed desirable to her, but which also supported her view of the world and thus her ideas about herself.

At the time, she had already known that Sabina’s existence as master builder Erwin von Steinbach’s daughter was not as uncontroversial as Schadaeus’ writings made it seem. Nevertheless, this old document had an awe-inspiring aura that had an almost uncanny effect on her. While reading the book and feeling the old paper under her fingers, she found it harder by the minute not to succumb and trust these words, printed four hundred years ago, completely and without reservation. At the end of the day, when she had thoroughly studied, surveyed and photographed the book, she had felt an almost friendly bond with it and she had been convinced that the book and its author had had the firm intention of conveying facts and knowledge truthfully.

Wherein an old chronicle is examined for a reference to Sabina

11.1 Specklin’s Chronicle, reprinting from 1890, Main Reading Room, Heidelberg University Library.

11.2—11.4 Rodolphe Reuss (ed.), Fragments des anciennes chroniques d’alsace. II. Les collectanées de Daniel Specklin, chronique strasbourgoise du seizième siècle, Strasbourg, Noiriel, 1890, Pages 131, 142 and 585.

Translation audio guide

To this day, W. said, she had not found any older source than Specklin’s chronicle that mentions Sabina the sculptress. Nor had she read anywhere about the possible existence of one. And yet, the later writing of Schadaeus from 1617 had made a greater impression on her. This was certainly due to the fact that the edition of Specklin’s chronicle that she had seen was a reprint from the 19th century, so that the document could not testify to the age of the written words by an equally old materiality. When she saw the fragile original of the Schadaeus script, on the other hand, she thought she could physically feel the past centuries with her fingers. Another reason for the greater impact and persuasiveness of the latter book was certainly the engraving by Isaac Brunn it contained, in which the Sabina inscription in the apostle’s hand can be seen. This pictorial source, perhaps the oldest, perhaps the only one, in any case the most frequently cited, was possibly even more important for the establishment of the belief in, or the knowledge of Sabina’s existence.

Whether the original manuscript of Specklin’s chronicle could have exerted a similarly intense physical persuasive force on W. is, regrettably, no longer verifiable. The so-called Collectanées, which were never published in their entirety, were destroyed in a devastating conflagration of the Strasbourg library in the course of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, along with many other valuable documents.

Wherein a board fence is photographed and what lies behind it can be seen in another photographer’s shot

12.1 Sabine Bengel, Das Straßburger Münster, Seine Ostteile und die Südquerhauswerkstatt,

(Strasbourg Cathedral: Its Eastern Parts and South Transept Workshop).

Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2011. Page 8 (detail).

12.2 Construction fence at Strasbourg Cathedral’s south transept portal, May 12, 2019.

12.3 Dr. Ernst Förster, Handbuch für Reisende in Deutschland, (Handbook for Travelers in Germany). Munich: Cotta, 1847. Page 461.

Translation audio guide

She still remembers very well her deep disappointment, W. said, when she traveled to Strasbourg for the first time in the summer of 2018, how she was looking for the south transept portal at the cathedral with the sculptures attributed to Sabina and instead had to stare at a construction fence behind which, it seemed to her in that first incredulous moment, everything she had come to Strasbourg for was hidden. A year later, she once again stood in front of the construction fence, and although she could have been prepared for it, to her own surprise, the feeling of disappointment set in much the same way as it had on her first visit. This disappointment was now compounded by an irritable impatience with the external circumstances that had hindered her from carrying out her project as planned.

What possibilities are there if what you want to see is not accessible? If what you want to photograph is unapproachable? At the time, she resorted to photographic material that others had taken before her, but she saw this as a mere makeshift solution, not without its flaws. She pointed to a photo she had taken of another photo printed in a publication. Among other things, the wall of Strasbourg Cathedral to the left of the south transept portal can be seen on it. In front of this wall, on a high pedestal, stands the sculpture of a female figure. She is poorly visible in the photo, and moreover, her head is completely obscured by the leaves of a tree. The photographer was obviously not interested in this sculpture, otherwise he would have moved a few steps to the right. Not much is missing, perhaps a meter, and the head of the female figure would have appeared behind the leaves.

The other photographer who is captured in the photo itself, however, is standing directly in front of the sculpture with his camera and tripod. He seems to be in motion, the steps leading up to the south transept portal are shimmering through his body: he must have been captured at the exact moment when he was about to choose a position from which he could best photograph the sculpture. More than a century later, she stood in roughly the same spot as that photographer, W. said. She would have liked to have the photo before her, which he had taken at that time, instead of her own photo of the construction fence. In the numerous publications she had scoured, she found virtually nothing about this sculpture of a woman, and at some point she happened to come across the Internet blog of a tourist who had visited Strasbourg Cathedral in 2011 and showed a frontal photo of this sculpture on her blog, accompanied by a caption stating that the woman depicted was 14th century sculptress Sabina von Steinbach.

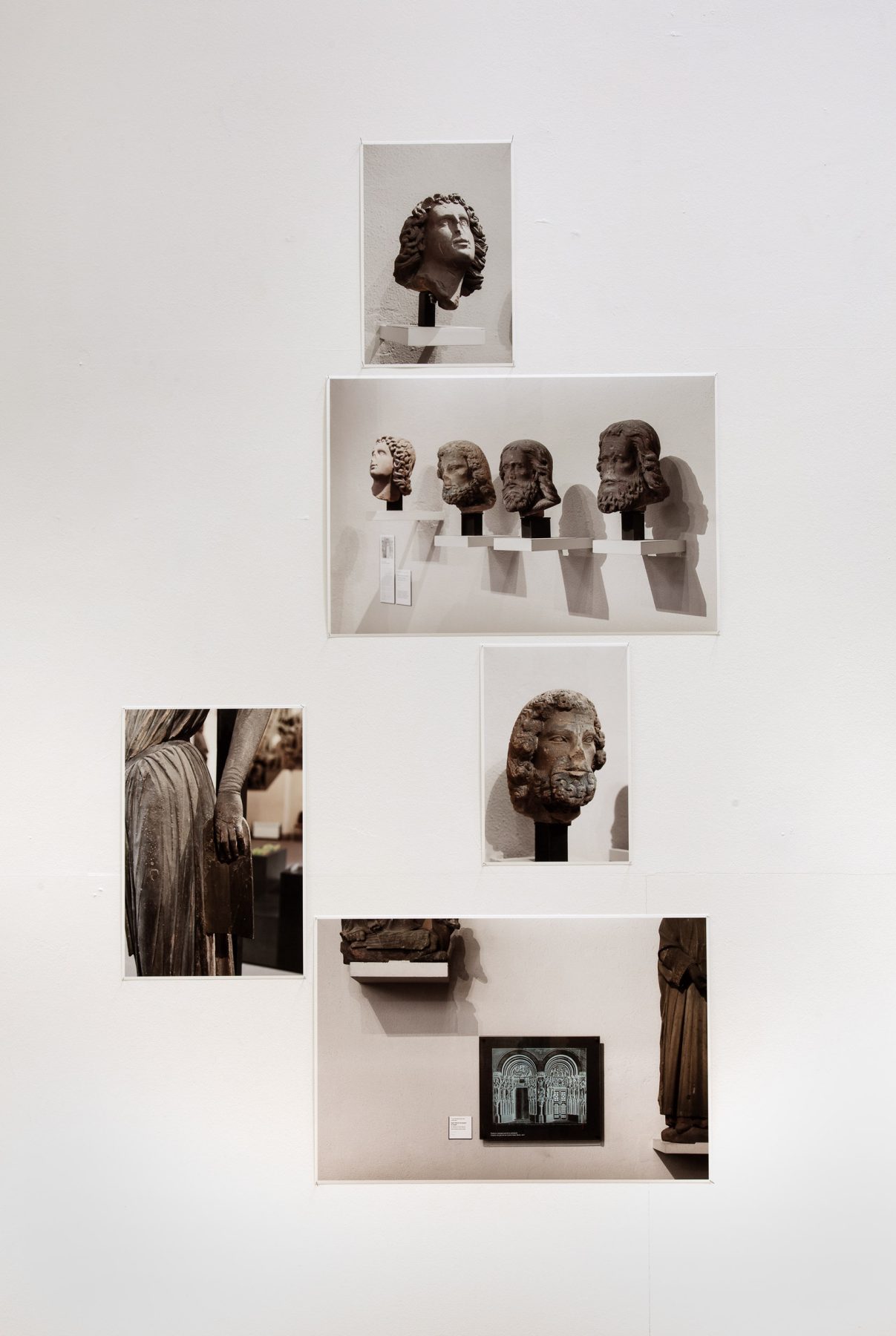

About what looking at an object long and hard can lead to

13.1 Hand of the Strasbourg Synagoga with Tablets of the Law, Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

13.2 Synagoga, Engraving by Isaac Brunn, reproduction, Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

13.3 Four Apostles’ heads, formerly part of the sculptures of the Strasbourg Cathedral’s south transept portal, Musée del’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

13.4 Apostle John’s head.

13.5 Apostle’s head created by Sabina?

Translation audio guide

Only a few weeks after her second visit to the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, she had traveled to Strasbourg for the third time, W. said. On this occasion, she mainly wanted to take a look at the four apostles’ heads, about which she had learned a number of new aspects in the meantime. Besides the apostles’ heads, there is an enlarged reproduction of the Brunn engraving in the museum, as W. mentioned to me almost casually at first, but then it turned out that she had actually studied this reproduction, printed as a negative, quite thoroughly.

Since the heads of the apostles were placed in the same room as the sculptures of the Ecclesia and Synagoga, she had, almost out of habit, turned first to these two central figures in the room. What she noticed then seemed to her very remarkable and very confusing at the same time. Several times that day she walked back and forth between the real Synagoga sculpture and the reproduction of the Brunn engraving and compared the smooth, blank Tablet of the Law in the sculpture’s hand with its representation in the engraving on which clearly dotted lines were recognizable. Of course, she asked herself whether it was possible that originally, still in Brunn’s time, a text could have been engraved on the tablet. She approached the sculpture as closely as possible; she would have liked to touch the tablet, to run her fingers over it, so that she would not have to trust only her eyes that nothing was hidden under this smoothness, no remains of a weathered text, no traces of a subsequent modification. But even if she did not verify this with her fingers, her judgment was unambiguous. There had never been a word on the Tablet of the Law in the hand of the Synagoga. This observation had somewhat puzzled her, since it implied that Isaac Brunn must have added the writing to his engraving, or the strokes imitating writing, that is. Brunn had thus added something without W. being able to understand why. She suddenly began to doubt whether Brunn was to be trusted as a visual chronicler, since quite obviously he had skewed reality on at least one occasion. At the same time, however, Brunn had Schadaeus, in whose writing this engraving was originally depicted, vouch for him, as did, of course, all his other contemporaries by virtue of not raising any objection to this depiction of the south transept portal of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Still, W. wondered, based on the missing writing on the Tablet of the Law in the real sculpture, whether it could have been that Brunn had added just as freely to the Savina inscription in the apostle’s hand. In fact, it had always irritated her how large, even huge, this inscription had appeared in relation to everything else. The scroll reaches from the apostle’s navel all the way to his feet, which struck her as an inappropriately obtrusive signature. However, the presence of this inscription was not only mentioned by Schadaeus, but also by Specklin in his Collectanées.

It was interesting, she added after a while, that even later she never encountered any text that, in all these centuries, had dealt with the discrepancy that existed between the smooth, blank Tablet of the Law in the hand of the actual Synagoga sculpture and the characters on the Tablet that are hinted at in Brunn’s engraving. Possibly these details were completely insignificant, but she herself was troubled by them to this day.

Finally, she turned her attention to the apostles’ heads, for which she had actually come to the museum that day. Like so many sculptures on and in France’s churches, a large number of the figures on Strasbourg Cathedral were destroyed, or at least they had disappeared during the French Revolution. Looters either took away parts of them or they were hidden so well in an attempt to protect them from the wrath of the revolutionaries that they could not be found again later. Of the 12 apostles of the south transept portal, none remained. Only a few heads could be retrieved later, and to this day there is disagreement about which of the apostles they belong to. The most important document for the attribution of the heads is still considered to be Isaac Brunn’s engraving from 1617, because this depiction of the south transept portal shows all twelve of them, each neatly in its place – and one of them holding the scroll with the Savina inscription in his hand. In many sources, especially older ones, this figure is referred to as the apostle John, although this is now considered to be incorrect. John can be identified as one of the beardless young men in the left wing, easily recognizable as an evangelist by the book he is holding in front of his chest. There are speculations that the apostle with the scroll could in fact be Thomas, elsewhere Paul is mentioned, yet other writings concede that it is impossible to know. When she revisited her own theory about the apostles’ heads that she had worked out in the museum, it often seemed to her quite elegant and convincing. She would have gladly surrendered to these moments and simply believed that Sabina, the sculptress, had actually existed and that the second apostle’s head in the row was her creation. But unfortunately, one, two, three contradictory arguments would invariably occur to her, interrupting this pleasant state of mind. No theory about Sabina, and possibly that was the only certainty she had obtained, was so flawless that it could not be reasonably contested.

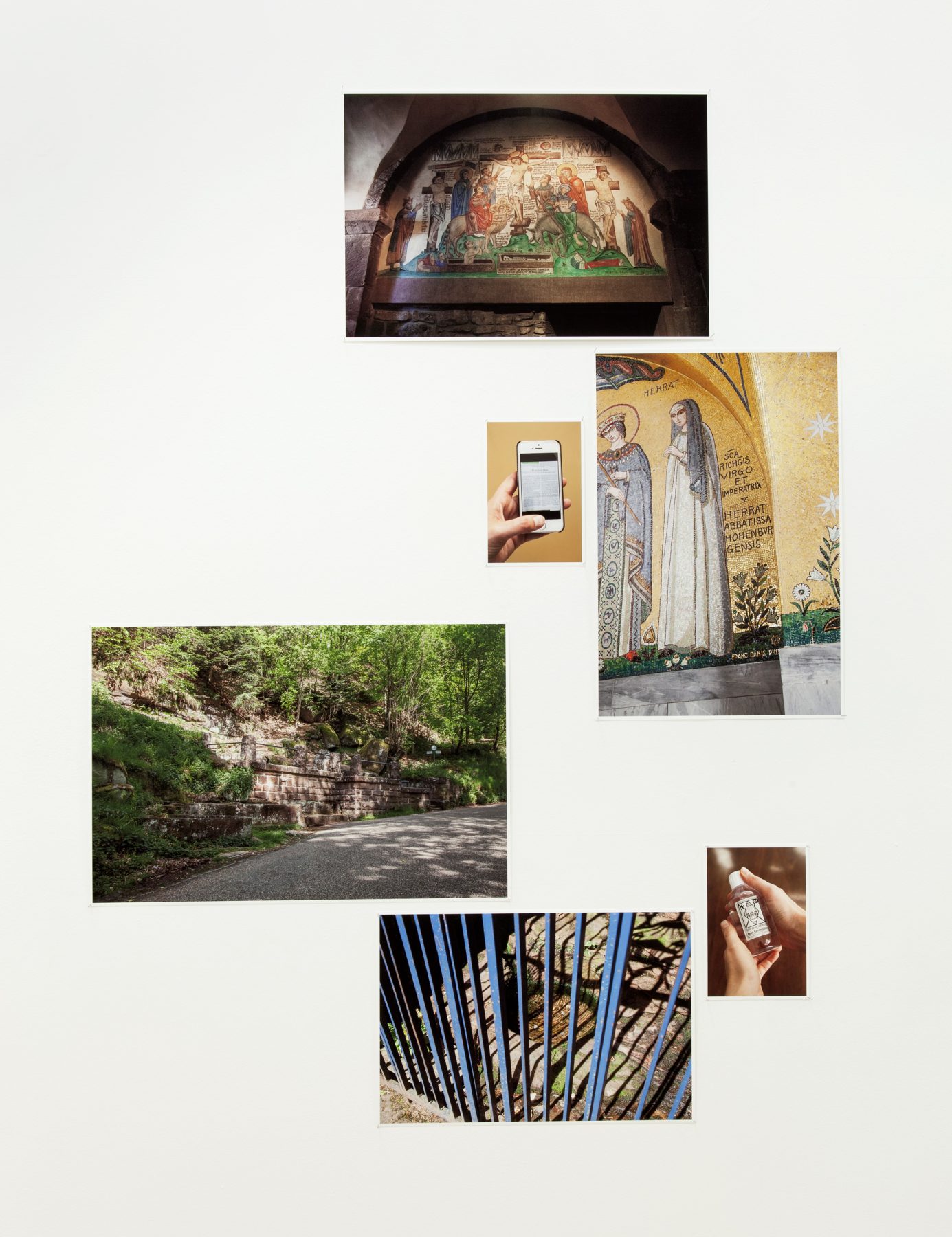

Wherein a special water and several extraordinary women surface

14.1 At the Spring of St. Odile.

14.2 The Spring of St. Odile.

14.3 Water from the Spring of St. Odile.

14.4 Fresco based on an illumination in Herrad von Landsberg’s Hortus Deliciarum, Hohenbourg Abbey.

14.5 Frau mit Blau (Woman with Blue), Süddeutsche Zeitung, January 15, 2019.

14.6 Mosaic by Herrad von Landsberg in the Chapel of Tears, Hohenbourg Castle.

Translation audio guide

She left very early that morning, W. said, parked the car below the monastery in a small, lonely parking lot mainly used by hikers, and followed the signs up a narrow path through a dense deciduous forest to Mont Sainte-Odile. There were, of course, many paths leading to the monastery of St. Odile. She no longer remembers whether she had deliberately chosen a path that would lead her past the spring first, or whether it happened by chance.

According to legend, St. Odile encountered a man blinded by an eye disease at this very spot, whereupon she struck her walking stick against a rock from which the spring, still bubbling today, immediately gushed forth. The blind man wet his eyes with the water and, according to legend, was immediately cured.

She still remembers the large woven basket, filled to the top with small plastic bottles, which, as a label said, contained water from the spring of St. Odile. The basket had stood in the monastery church at Hohenbourg and although she had already filled some of the water into an empty sparkling water bottle at the spring below the monastery, she found these bottles, which probably never contained anything other than water from St Odile’s spring, so pleasing that she absolutely had to take one of them along with her.

St. Odile’s tomb is located in a small, freely accessible room in the monastery building. She remembers spending some time there, W. said, sitting on a small wooden bench in front of the coffin containing her remains and looking at the cycle of paintings telling the story of Odile’s life. In the green notebook, however, there was no entry on this. Instead, she had taken all the more notes on the fresco, which she had come across during her wanderings through the monastery building.

The fresco’s subject originated from a medieval encyclopedia entitled Hortus Deliciarum, written around 1175 by Herrad von Landsberg, abbess of the Hohenbourg monastery at the time. The valuable manuscript was kept in the monastery until the middle of the 16th century, and thereafter in various places in Strasbourg. Later on, it was stored in the university library there, where it was destroyed by major fires during the siege of Strasbourg in the Franco-Prussian War on August 24, 1870, along with numerous other art treasures in museums and libraries. Copies, facsimiles and transcripts have been preserved until today, which allow for a reconstruction, or at least an idea, of what the Hortus Deliciarum looked like.

In the monastery yard are several small chapels on the edge of the rocky plateau. By a strange coincidence, W. had received a message on her phone the very moment she entered the so-called Chapel of Tears and discovered Herrad von Landsberg’s mosaic there. The message contained a photo of a newspaper article that spoke of a medieval nun whose teeth had blue tartar, which was recently discovered during the examination of her remains. At the time, W. said, she wondered if one could only ever discover something when it was culturally conceivable, and therefore also conceivable for oneself. Of course, it was not proven that the nun with the blue tartar had produced any sophisticated illustrations. But it seemed to her, there in the Chapel of Tears of the Hohenbourg, that this nun could have done just that, and she felt a certain gratitude at the thought of living in a present that was looking for such clues to the activities of women in past times.

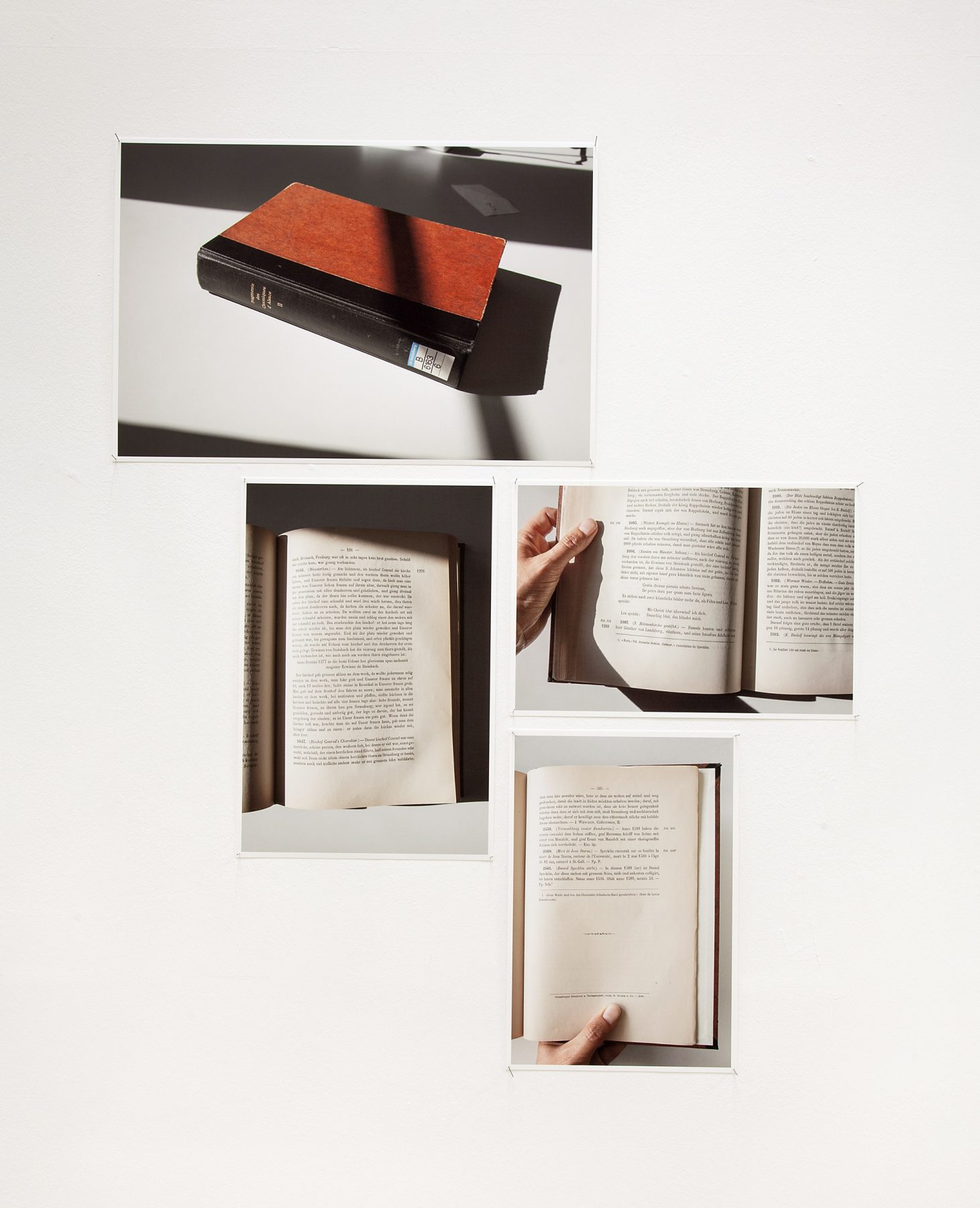

Wherein two similar chapters in two different books are examined and a third one calls everything into question

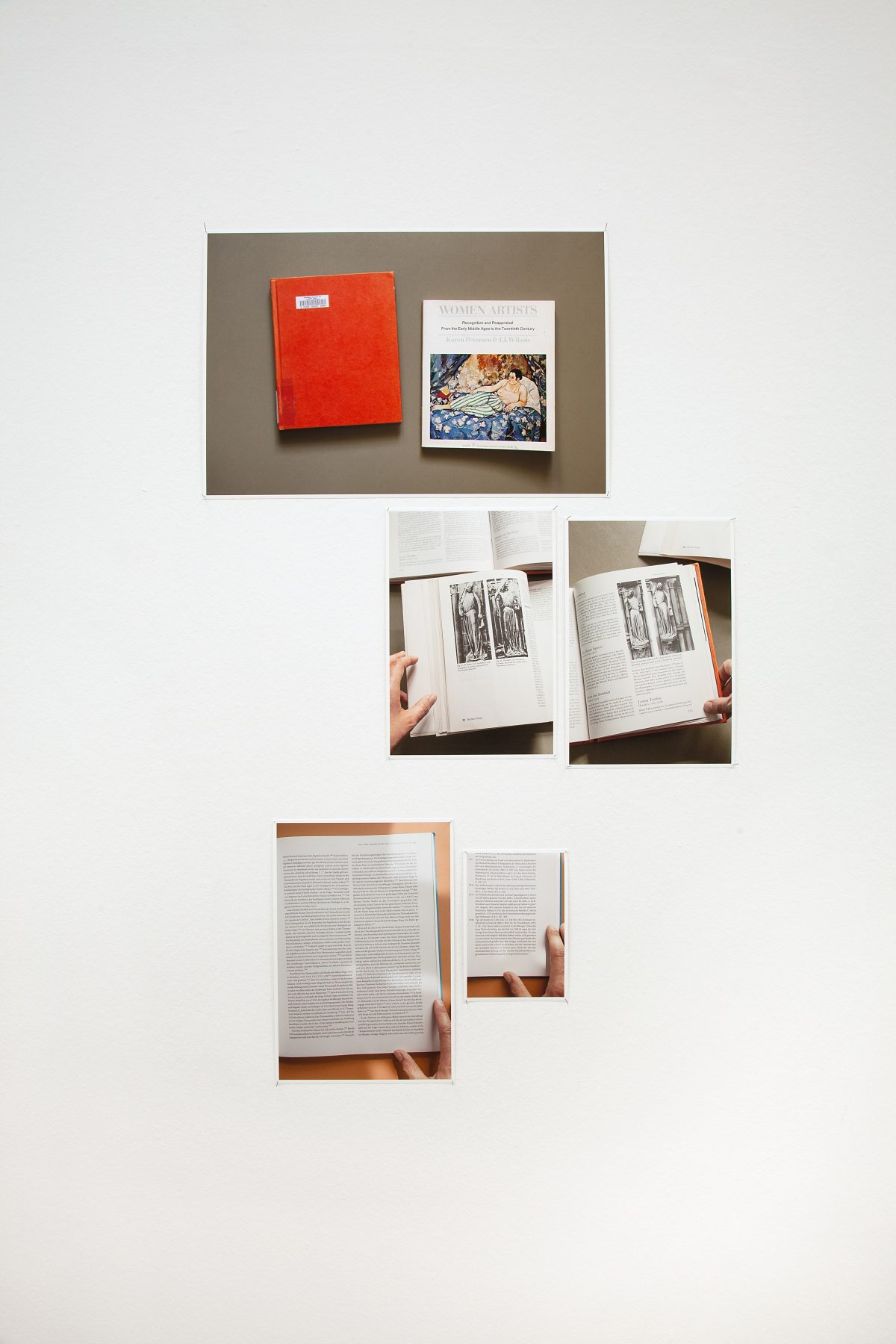

15.1 Two books in W.’s Study: Women of Achievement, Women Artists.

15.2 Karen Peterson and J. J. Wilson, Women Artists, Recognition and Reappraisal from the Early Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century, New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1976. Page 20.

15.3 Susan Raven and Alison Weir, Women of Achievement,Thirty-five Centuries of History, 1981, London: Harmony Books. Page 213.

15.3—15.4 Sabine Bengel, Das Straßburger Münster, Seine Ostteile und die Südquerhauswerkstatt (Strasbourg Cathedral: Its Eastern Parts and South Transept Workshop). Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2011. Page 201 and footnote 1940.

Translation audio guide

The two English-language books on the women’s movement of the 1970s and 80s that include Sabina von Steinbach in their canon are remarkably uncritical. Not only do they give an abridged account of what was known about Sabina von Steinbach’s existence at the time, but they are most likely incorrect, and in any case highly unscholarly. The sources referred to by the authors are also not mentioned, or are cited only inadequately. One might ask whether this has not done more harm than good to the women’s cause, and this question has probably been asked several times already, W. said. She was also surprised that Sabina von Steinbach was still mentioned without much thought as late as the 1970s, early 80s, especially as the creator of the two sculptures of Ecclesia and Synagoga. The authors could have known better. They could have mentioned that it was not actually known whether and which sculptures were created by a certain medieval sculptress named Sabina and who she actually was. But they did not. W. admitted that this had irritated her, along with the tone the texts are largely written in. And, of course, it made her read the accounts of the other women mentioned in the books more critically, even skeptically.

Nevertheless, W. said, books like these were important at the time, and perhaps, she added, it did not matter, or was even quite all right, that the women’s movement had used Sabina von Steinbach for its purposes, even if she did not exist as such. Sabina von Steinbach has been instrumentalized so often over the centuries, especially by male authors, for German nationalist purposes, as a manifestation of a female stereotype – would it not be a kind of compensatory justice if Sabina had also contributed to the equality of women?

Later, W. admitted that this could of course only apply conditionally, if at all, and that it would be important, of course, to check all statements and assertions for their correctness – and if that was impossible, to point them out accordingly. In fact, she added, she herself had been tempted to create her own Sabina the way she wanted her to be and the way she found her to be useful. The different existing interpretations of Sabina show how easy this was precisely because so little was known about her. In the end, however, the different interpretations almost always revealed more about the author’s worldview and desires than they did about Sabina.

W.’s recurrent preoccupation with the question of whether there could be any safe criteria for distinguishing between real and fictional persons had each time filled her with a great perplexity, which not only led to an uneasy blankness in her mind, but in which Sabina von Steinbach also seemed to dissolve in a way that she had only once experienced in a similar way before, when reading a book from 2011 that was written by a contemporary Sabine with the surname of Bengel. W. had studied her doctoral thesis on the Strasbourg south transept portal for the first time at the State Library in Karlsruhe and at the end of that day she had realized not only that Sabina von Steinbach had disappeared but also the other sculptress Sabina, who supposedly lived a hundred years earlier. The only thing that remained from that day was the assumption that the Savina named in the Latin inscription was a benefactress who possibly belonged to a Strasbourg family of burghers named Kalb. However, this was not a historical fact either, but an assumption that the author Sabine Bengel had made on the basis of her own research. W. admitted that a feeling of disappointment had begun to creep up in her after reading this. Of course, part of her had been well aware from the beginning that her research might not bring her any closer to the sculptress Sabina. However, she had not really considered that the sculptress could not only undergo changes or even withdraw, but that she might dissolve altogether. Her undertakings probably never felt more futile on any day than they did then, even though, as her notebook entries repeatedly attested, she had often felt doubts.

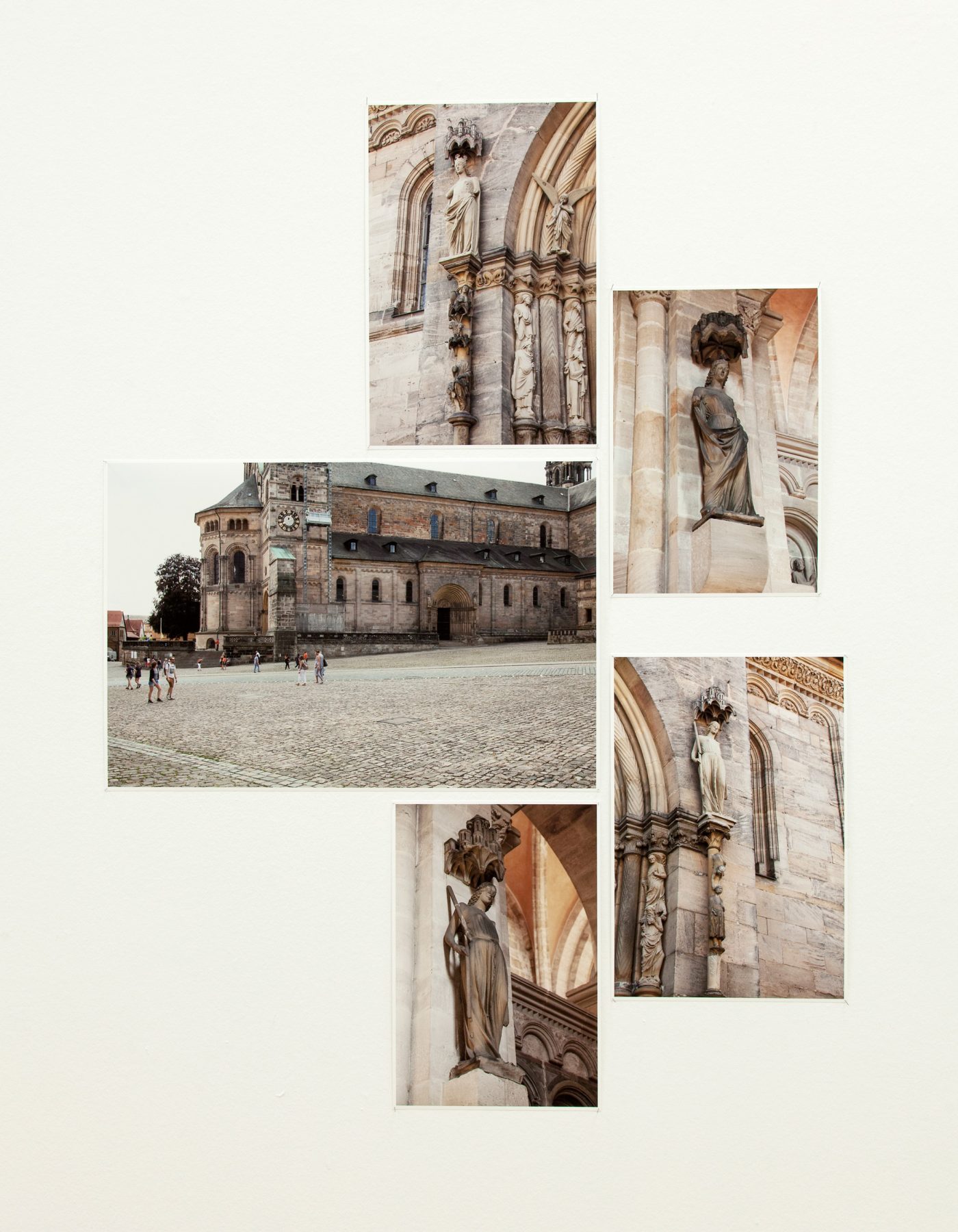

About the comparison of some medieval sculptures in different cities and a growing uneasiness when looking at them

16.1 Cathedral Square, Bamberg.

16.2—16.3 Ecclesia and Synagoga (reproductions), Prince’s Portal, Bamberg Cathedral.

16.4—16.5 Ecclesia and Synagoga (originals), Bamberg Cathedral interior.

Translation audio guide

She spent some time on Cathedral Square in Bamberg, W. said, and the longer she stayed there, the more the sculptures of Ecclesia and Synagoga on the prince’s portal bothered her. At Strasbourg Cathedral, she said, she had really never fully grasped the original context of the sculptures, as she finally realized there, on Cathedral Square in Bamberg. During each of her visits to Strasbourg, the south transept portal was obscured by a tall construction fence. She wondered whether it was due to her own lack of imagination that she only really came to comprehend the meaning of the sculptures on the entrance portals of the cathedrals when she herself physically stood in front of them in Bamberg. It was as if she had gained a theoretical understanding of the sculptures in their original context through the illustrations in books and the descriptions in texts, but this impression remained incomplete without her own sensory experience. Only her own seeing on site had enabled her to grasp the original context on a level of her mind that she could best describe as a visual level of cognition.

While she was sitting on Cathedral Square in Bamberg, she actually let the two sculptures on the prince’s portal have a very thorough effect on her and after a while she asked herself why these figures, which are easily recognizable as replicas, standing out brightly from the rest of the façade, had been placed there at all. The originals had already been removed from their initial context, both in Strasbourg and in Bamberg. First of all, of course, to protect them from the elements – but beyond this, would a museum not be a more appropriate context today anyway? She found it increasingly absurd that the original, 800-year-old anti-Jewish statements had been repeated once again in the copies. At this point, I recall, I objected, noting that W., as she herself had pointed out, did not really realize the impact of these sculptures until she was on Bamberg Cathedral Square and saw the prince‘s portal and with it the sculptures in their original context. This, however, proved how necessary and helpful it was for the understanding of historical contexts and realities to preserve the original contexts and to allow even difficult representations to continue to exist.

To this, W. replied that until recently she probably would have agreed with me completely and that she still did to some extent. Perhaps she had just been sitting on Cathedral Square in Bamberg for too long, but now she couldn’t shake the thought that if it were her house, she wouldn’t see why she should have anti-Jewish sculptures hanging there, just because some ancestors had put them there several centuries ago. In the case of Bamberg, the issue not only concerned the depiction of the Synagoga. Even more problematic was the very obvious anti-Jewish imagery on the column below the sculpture of the Synagoga: a figure of a devil blindfolding a Jewish man. I had not even been aware of these two figures in the photographs until W. brought them to my attention, and I am not sure I would have noticed and understood them on my own.

“Why not put up an explanation on a plaque that critically engages with the context?” I asked. W. did not respond to this suggestion directly, instead she told me about her visit to the historical museum adjacent to Bamberg Cathedral. During her visit, a special exhibition on the second floor called Jewish Life in Bamberg was on display. In the very first room of the exhibition, she was once again confronted with the sculptures of the Ecclesia and Synagoga, which were set up as original-sized plaster casts, for W. the third version of the figures that day. These brilliant white plaster representations were accompanied by an explanatory text outlining how medieval Christian theology had disseminated anti-Jewish ideas to promote its own doctrine of salvation and to demonstrate its superiority. According to the text, this perception was firmly embedded in the minds of the predominantly Christian population of the time. The contrast between the critical examination of the sculptures in the exhibition and the uncritical presentation at the cathedral, whose prince’s portal she could see through the window of the museum, indeed seemed somewhat surreal to W. But it was, of course, a coincidence that she felt this way, since the exhibition was only temporary and was only on view for a few months. Certainly, the fact that she had been the only visitor during her stay had reinforced the impression, which was not only contradictory but also unreal.

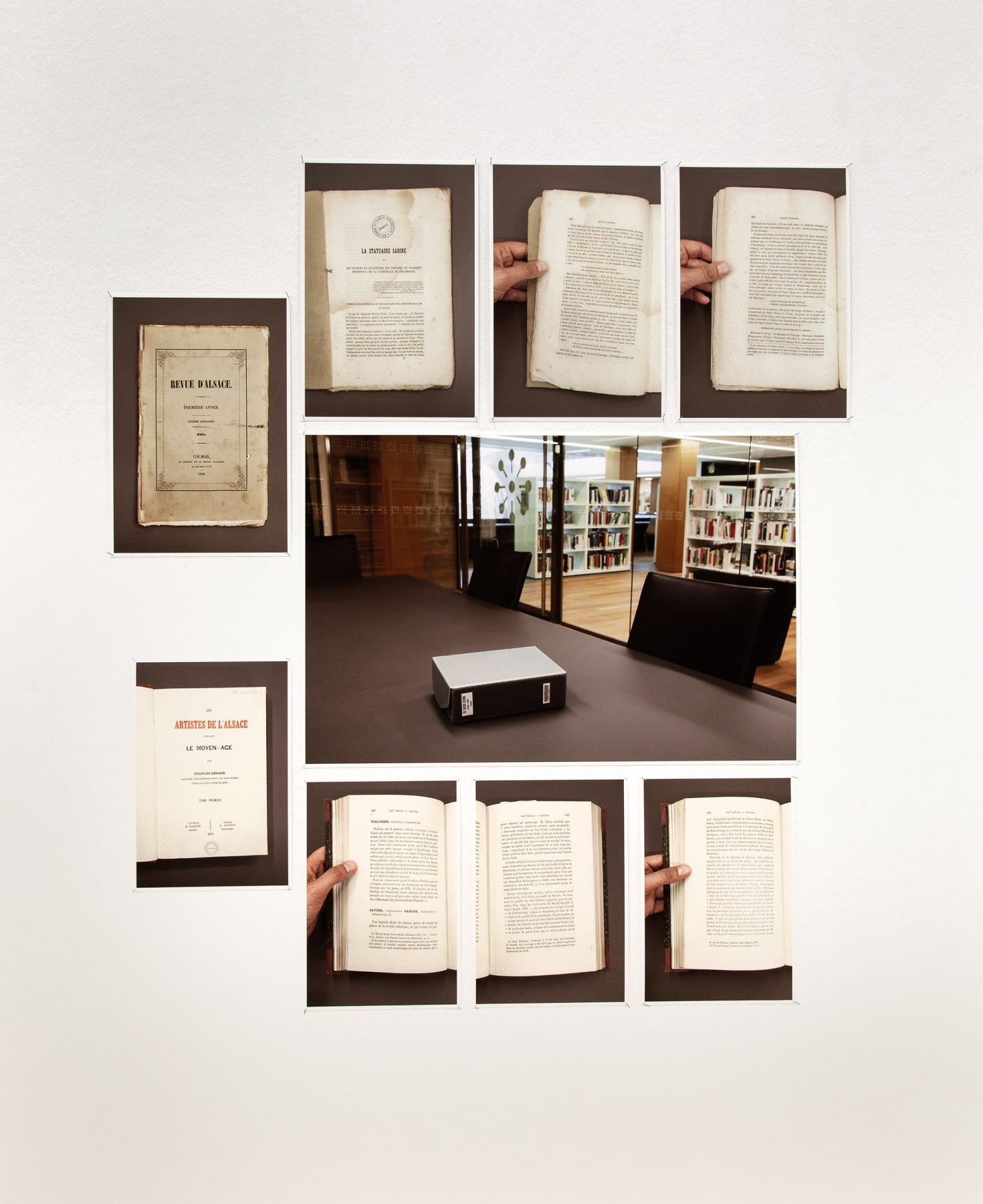

Wherein two texts from the 19th century are extensively studied and compared

17.1 Reading room, Bibliothèque Nationale et Universitaire.

17.2 Revue d’Alsace, Colmar, 1850.

17.3—17.5 Louis Schneegans, La statuaire Sabine (The Sculptress Sabina) in Revue d’Alsace. Colmar, 1850, Pages 1, 262 and 290.

17.6—17.9 Charles Gérard, Les artistes de l’Alsace pendant le moyen-age, Colmar: Barth, 1872. Title page and pages 100, 103 and 110.

Translation audio guide

She had been trying for a long time to get hold of the Revue d’Alsace containing Louis Schneegans’ text about Sabina through other means, W. said, but only in the Bibliothèque Nationale et Universitaire in Strasbourg she was able to locate an original of this journal.

In addition to Schneegans’ text, she was also able to study Charles Gérard’s detailed treatise on Sabina. Due to this simultaneous reading, a comparison of the two texts turned out to be virtually inevitable.

Obviously, Gérard, whose writing had appeared a good twenty years after Schneegans‘, had also studied the latter‘s treatise thoroughly. He follows all points of Schneegans’ argument down to the last detail in favor of the existence of a sculptress Sabina, who supposedly lived 100 years earlier than generally assumed until then. W. often had the impression of reading in Gérard’s work a rephrased version of Schneegans’ words, as if his text was an echo that sounded 20 years after the publication of the first text.

According to W., she was not aware that already in Schneegans’ time the theory was common that the Sabina mentioned in the inscription, was not interpreted as the sculptures creator, but rather as their benefactress. Schneegans clearly contradicted this assumption without seeing any reason to address it any further. This, however, does not change the fact that the benefactress theory is currently probably the most common and widely accepted one among art scholars, although few people and hardly anyone seem to be seriously concerned with Sabina.

She found it astonishing how Schneegans, in the course of a two-page argument, moved from what she still considered a somewhat speculative theory to near certainty that the architect Hermann Auriga must have been sculptress Sabina’s father. It seemed to her that Schneegans, inspired by the beauty of his own reflections, forgot that he alone entertained this idea and that it was based on nothing more than his own conceit. Although Schneegans admitted at the end of his remarks that he had no evidence for his assumption, it did not surprise her to read that Charles Gérard had also adopted this theory of Schneegans and confirmed it as the one most likely to be true.

Wherein, upon reading a dissertation, an altered date is revealed and another Sabina is discovered that had long been overlooked

18.1 Front view of Alte Nationalgalerie with frieze by Moritz Schulz.

18.2 Frieze by Moritz Schulz (detail), Alte Nationalgalerie.

18.3—18.4 Hartmut Dorgerloh, Die Nationalgalerie in Berlin, Zur Geschichte des Gebäudes auf der Museumsinsel 1841—1970 (Berlin’s National Gallery: The Building’s History on Museum Island 1841—1970), Doctoral thesis, Faculty of Philosophy, Humboldt University of Berlin, 1997. Pages 83 and 108 (detail).

Translation audio guide

It was only long after she had discovered the other Sabina on the frieze in the stairwell of the Alte Nationalgalerie that she came across the fact that Sabina had appeared yet another time, on a second frieze in or rather on the National Gallery in a dissertation from the 1990s on the history of the building’s origins. This second frieze is located high above the main entrance, in the so-called vestibule, which has not been open to the public for a long time. Basically, therefore, it was not surprising, W. said, that she had never noticed this Sabina before. Still, her own ignorance made her realize how easy it was to overlook something, how incomplete her research had always been and how little she actually still knew.

When she finally looked at this frieze on the façade, standing as close as possible to it, halfway up the stairs in front of the closed gate, looking at the figure of Sabina with binoculars, a question that had been on her mind all along, at least subliminally, but had been overshadowed by other events and questions, forced itself upon her again. This question, as she came to realize there with absolute clarity, had always been the actual, the central question. It had been the impetus for taking up all her research. From that point on, it seemed absolutely imperative to her to find out who was responsible for the decision to include Sabina in the two friezes of figures in the Berliner Nationalgalerie. The answer to this question had seemed to her for some time like the necessary key to a form of insight that would allow her to get through to her own present and actually understand it. This hope, which in retrospect may seem somewhat naïve, drove her to search for and study in detail various texts about that period and about those responsible for the Nationalgalerie’s establishment.

However, it did not lead her to the hoped-for answer to her question, which may have been due to the fact that this question was hardly ever asked by any of the texts, on the one hand. On the other hand, this may have been because it seemed that actually no documents survived or existed at all in which the process of selecting the persons for the figure friezes was documented.

At some point, she began to dream of a group of gentlemen, W. continued after a short pause, of men who had been responsible for the design and the construction of the Nationalgalerie in the 1870s. She still wakes up sometimes at night with the vivid image in her mind of these gentlemen sitting there, in Berlin’s City Palace, in the former study of Frederick William IV, who had died shortly before. In her dream, she would watch them discuss in an awkward fashion and at length whether to include the sculptress Sabina von Steinbach in the friezes of figures planned for the Nationalgalerie. Sometimes the gentlemen would continue their discussion while W. dozed off in a kind of half-sleep, and then it could happen that this situation seemed more real to her than the present, to which she returned in the morning.